Ai WeiWei: Never Sorry

Ai WeiWei has such a different perspective from any American artist because of how his life began. Living in a family who was exiled to strenuous labor for defying the government is an extreme circumstance which he took as inspiration. The mistreatment that China has for its people for the sake of the government and preserving power over well-being is disgraceful but difficult to ‘fix.’ The approaches WeiWei takes throughout the years to portray his beliefs and feelings towards the governments are informed by more than his experiences in China. When he went to school in New York City he was exposed to democracy and artists who had the freedom to create volatile pieces of work. The ability to think openly and freely was important for his development and allowed him to create pieces which could ignite a fire in those who thought freely in China, or to open others up to the concept of different ideas who had not thought it possible before. I am vastly inspired by his dedication to being an activist, even when it meant he would be imprisoned for months. When he gave the finger to Tiananmen square and then the Eiffel Tower, U.S. Capital and more and dropped the Han Dynasty Vases in protest to what they all represent, I could feel the passion he held within the photographs. The boldness of the statements he made exemplified the courage he had, but also as he states the fear he has. These symbols which represent oppression, violence, and inequality still threaten our societies today because they stand as symbols of honor and pride.

Although he says he is afraid I believe the fear fuels a type of passion which cannot be recreated without fear. It is a channeled anger which is informed and manipulated in a way to convey meaning. I admire his acknowledgement that the road to social justice, especially in China will not be easy or short, but this gives him even more reason to continue. I think it is wonderfully clever the way in which he filmed many events he took part in, especially the dinner he announced and supporters attended. These people were brave because they were being caught on his film as well as the government’s film. They spoke about the publicness of the footage he captures and how it can influence those who view it, but the government’s footage will never be released. So, when his videographer began filming the government videographer’s camera from behind I could not help but laugh at the genius in the idea. Although our government is much more open, there is so much the American government hides as well. This resonates with the secrecy that could ruin the power of the government if those secrets were released. From what I know, China shares almost nothing with the public, largely skewing their perception of what goes on behind the scenes. This came into play with WeiWei when he was imprisoned. He comes off as such a confident person that after he was released I was surprised at his inability to give details of what happened and why to his supporters who demanded his release. It felt as if something had changed because of threats and the fact that he has people he cares about that they could potentially hurt. Through his work I learned that fear and anger must be channeled in a purposeful way with deep consideration on how it will be taken by those who need to see it, as well as those who will want you to disappear after they see it. Power struggle is not an easy battle to fight, and WeiWei fights out of fear of China’s non-transparency.

Dawound Bey on Visualizing History

Dawound Bey reimagines history in a stunningly powerful way. There is so much to unpack in such a short time frame in this documentary. I am amazed at the way he sought to reinterpret African American history to “resonate in the contemporary moment.” For his first body of work which was shown in the Birmingham Museum of Art he took inspiration from the lack of African American input at the Harlem Museum; and more prominently the absolutely horrifying bombing of the Baptist church on a Sunday which robbed six children of their lives. The way he noticed how the community's perspective was missing and the need to take ownership and power back from the narrative of the bombing is essential to his work. He took this incident and sought to portray how young these children were through the portraits of young African American children who were the same age as the children who were murdered. Although, he felt this work was incomplete. He points out that the passage of time was missing from the feeling he wished to evoke from this work. As a result he created diptychs of the portrayed children next to portraits of African American adults who were the same age as they would have been at the time, had they gotten the chance to live their lives. He elevated the emphasis on the lost possibility that they never became. This was powerful to those who visited the Birmingham Museum of Art not only because the African American community is prominent in the area, but at the time the people who visited could remember a time when they were not allowed in that same museum. This is the first time I have seen a body of work study and display the passage of time in this way on such an explosively emotional subject. The way he highlights the possibility which was robbed of the children in a diptych where the subjects mirror one another at vastly different ages is heartbreaking. What a powerful way to redisplay such a horrific act to the public with many layers of emotion and meaning, in the contemporary moment.

Bey’s next body of work was inspired by his desire to reimagine the fugitive landscape during the time surrounding enslavement, as well as a line from Langston Hughe’s poem “Dream Variations'' which read, “Night coming tenderly / Black like me.” He resonated strongly with the word ‘tenderly’ in the way that night is usually thought of as scary, but it wasn’t for the fugitives. Finding such inspiration from another artist who works with words and expanding from that point is something I have never seen done so intimately. At first glance I thought it was strange how underexposed and dark the photographs appeared, but the meaning behind it is so powerful it redefines what makes a photograph beautiful; and how the purpose of the work is more important than a pristine, well lit shot. He sought to capture minimal visibility to mimic how it felt to move through the landscape late in the night. His photographs were printed large in scale to be able move into the space which was shown. To engage with it and slow down. I found it fascinating how he idealized the gallery as his partner in making his work. The making of it is important of course, but the interactions in the active space gives it a purpose to others. His use of space and wish to create a more accessible gallery culture is truly amazing.

Manufactured Landscapes by Edward Burtynsky

The way Burtynsky explores our relationship with nature and how nature is not really separate from us is such a unique perspective. Especially since he believes we must first observe in order to create art. This idea struck me. I feel as if when I get into a creative block I need to search for my next inspiration and what to do next, but really, observing is the best first step an artist can take. Inspiration is found in the moments when we relax. I thought it was very interesting how he resonated with the extractions in our landscapes when he saw a scene on an unexpected day. This scene then inspired him to find industrial incursions created by our extractions in the landscapes. These are scenes that many of us pretend do not exist because they are such obvious destructions and disregard for the planet. It is the same as how we all buy clothes at the store and use oil even though most of us know, at least in the back of our minds, that the people who supply us these goods are disgustingly underpaid and treated poorly. I always seek out the beauty in the planet, so when I saw his approach I thought, wow what a refreshing take on the reality of our effect on and relationship with nature.

When he dives into processes of creating manufactured goods and the management of the waste they consequently create in asian countries, he is exposing a human rights issue that many people pretend does not exist. I think of this as how we, as a society, are so comfortable with the goods we have in a capitalist environment that we have no regard for how it got here, and when it is exposed we are more concerned with losing our goods than helping the people we exploit as a result of our greed. I admire how Burtynsky displays his works with minimal opinion on how one should view the work. He does not say this is disgusting and wrong and we need to change our system because allowing people to see this on their own creates a deeper impact. By having a purpose behind the project with research and a goal and allowing others to decide how to interpret it on their own, Burtynsky creates a true work of art. When something is explained and interpreted for you there is no room for differing opinions, whether they are in the direction the artist was hoping for, or not. I find this aspect of his art extremely important to the outcome. While watching the documentary I felt so heartbroken for the workers, especially since it is a normal work life for them, and some feel that it is their duty to their country. This extends to the idea of freedom and how certain countries do not allow their citizens to have open, free thinking. This drastically affects the way society flows and how opportunities are viewed. If you are never allowed to think a certain way, or are comfortable with restrictions how will change ever happen? This reminds me of the concept “things just are the way they are,” when in reality everything has a reasoning behind it or something that caused the event or thought to happen. Whether we can ever know why or not, exploring the ‘why’ is important to progress. The connections I made may not have been exactly what Burtynsky intended, but that is the beauty of this work.

Additionally I admire the way he works with other people. He approaches situations in a firm but respectful manner. He is confident in his work, himself and the people he surrounds himself with for projects, which I believe is why he was able to travel and get access to so many unique locations. These locations especially emphasize the terrible qualities of the countries he visits, which I assume they do not want the public to know about. Burtynsky’s research behind each photograph about the location, conditions, lighting and more affect how his work is portrayed. I found it very interesting when he delved into the mental health of the workers, which shows through in his work. He creates portraits and landscape shots which portray his ideas on the manufactured landscape in vastly differently, impactful ways. I think I especially learned how extensive research elevates artwork in a unique way.

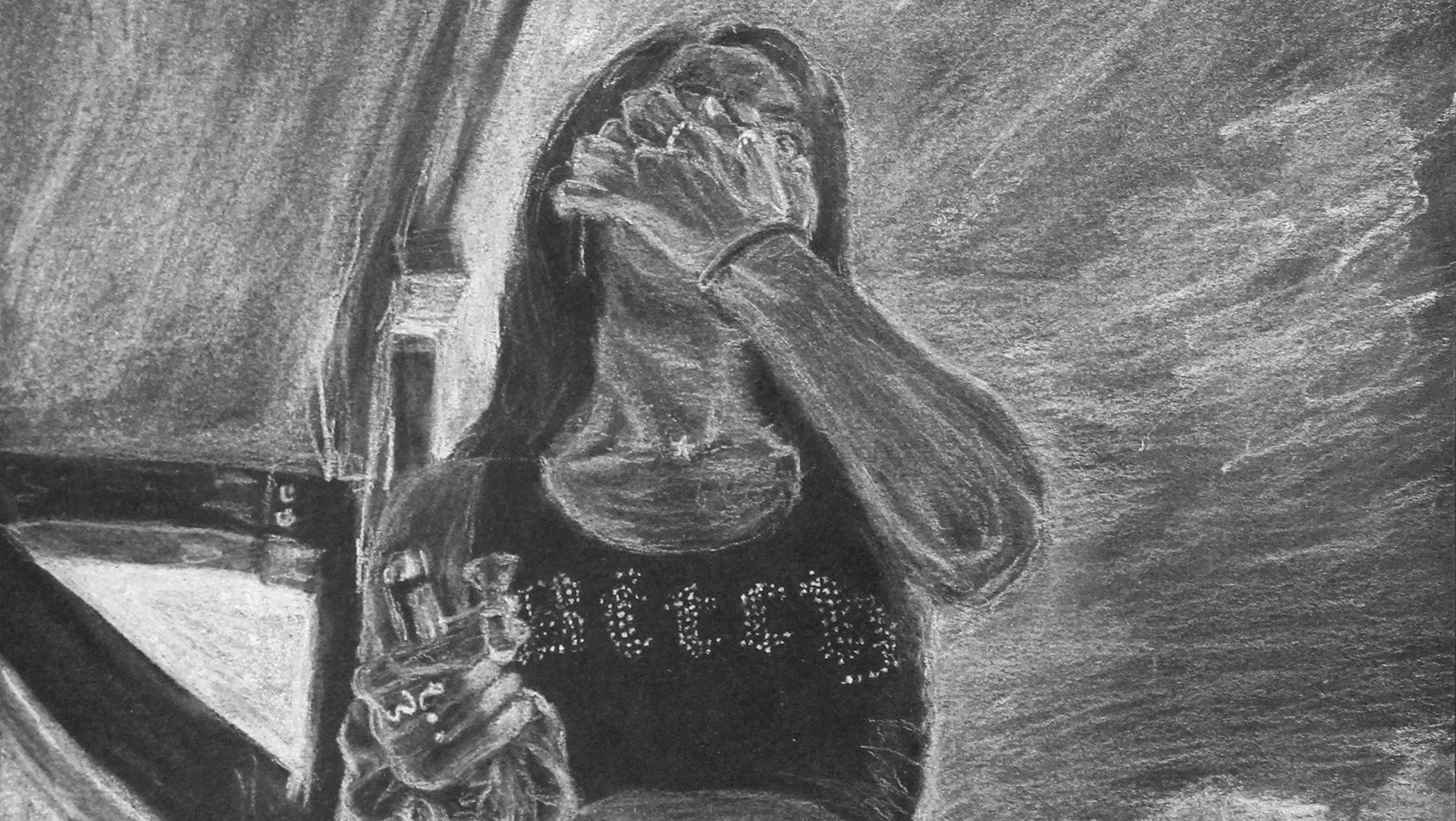

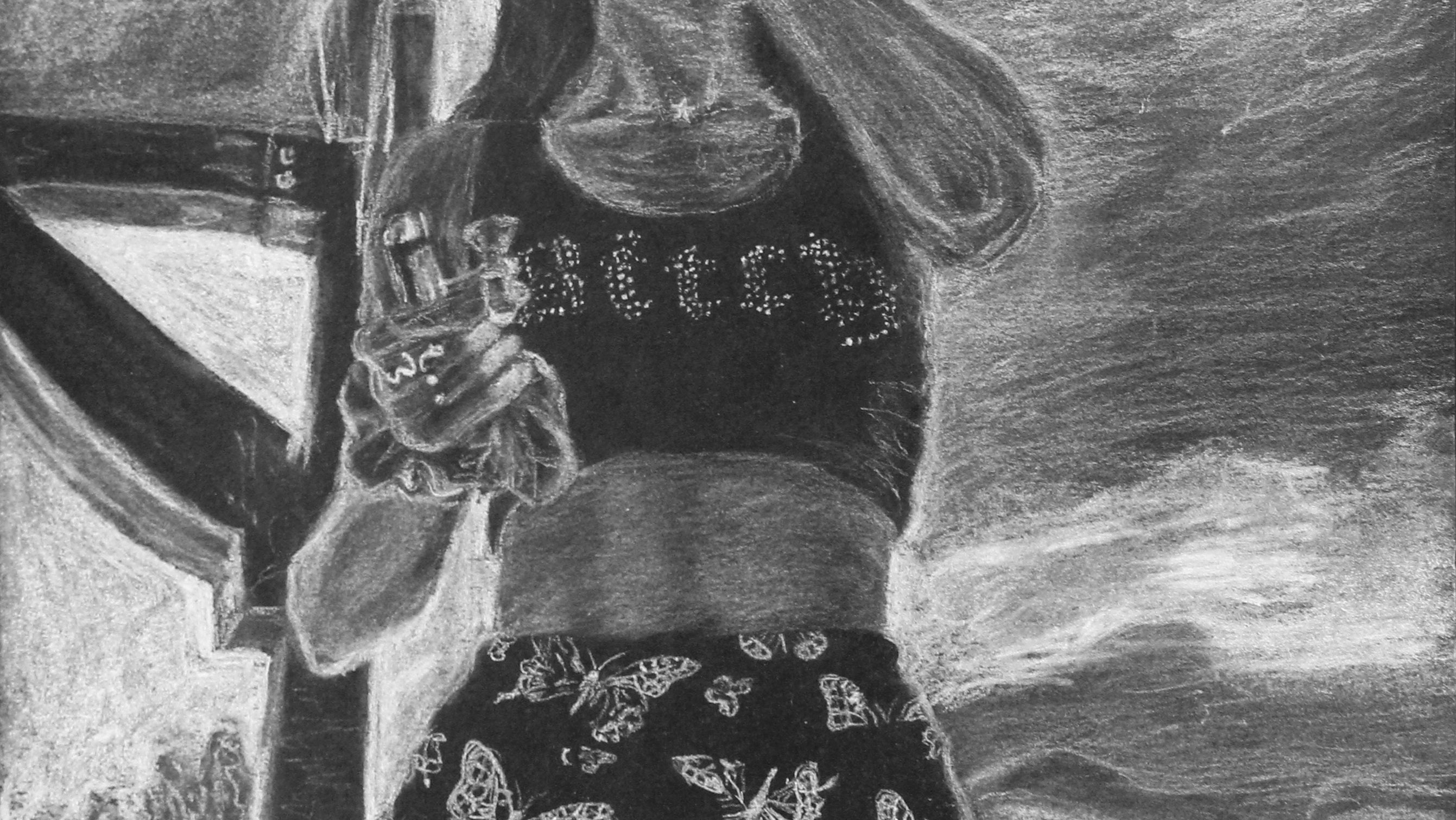

What Remains: The Life and Work of Photography Sally Mann

I find Sally Mann’s stance that if you’re not photographing what you love it won’t be your best work extremely intriguing. As well as that she believes you photograph the things closest to you the best. I think that creating art is such a personal experience and I have always found exploring the most interesting to myself, but the recent work I have created has shined so brightly because it is about my personal human condition. I think that each belief she holds elevates her work to a personal engaging level that you cannot have if you are not connected to what you are creating. Additionally she has a philosophy that you don’t need to leave home to make art, but rather you can find it in your everyday life. She began doing this with her children and realized the potential she had in seeing images within them. How she describes seeing the world in images, as her husband describes her ability to just see and image before going out to capture it emphasizes the idea that in the ordinary is beauty. I think there is a particular type of power in utilizing “the local,” as she calls it, to accurately portray the life in which your perspective stems from. No person has the same exact perspective as the next, which consists of the surroundings and extenuating circumstances each person lives with. Her mindset on art inspired me to think deeper about my surrounding and family and how they affect my life everyday and over time.

I resonated with the pressure she described with making work and then feeling as if the next photograph or body of photographs needs to be better than the previous one. The feeling of having to subvert from yourself and past work. Although I think her work shows that the next body of work does not necessarily have to be ‘better,’ but have the same amount of passion. She transitions smoothly from photographing her children to landscapes as she moved them further and further from the camera into the landscape. Change is inevitable and seeing how her eye found images differently over time is fascinating.

When she found herself having to explore what she wants to leave behind as an artist, diving into what is okay to shoot and show to the world for open interpretation I saw a reflection of my own thoughts as an artist. At the time she was speaking about exploring her husband’s rare form of muscular dystrophy, whereas I struggle with my passion to explore class disparities and the homeless condition. There is the worry of creating something that comes of, or treats the people in a way that is vapid and cruel. Lifting up oneself through creation by exploiting a terrible condition. Although through Mann’s work I saw such a personal, wholesome and pure connection with her work. Memories come across through the people who are important to her and involved in her life and creation.

Her work took a sharp turn when a prisoner escaped and committed suicide on her farmland to avoid being shot or taken back to prison. She was forced to have a perspective, relationship or at least thoughts about death. As humans we are all mortal, but thinking deeply about it scares most of us, so we avoid it or believe in things that make it less threatening. She saw how Americans specifically treat death as something ugly and undesirable to talk about. We do not want to see death as an organic part of life and would rather hide from it. This event pushed a radical impact on how she thought of the land she owned. Her openness of talking about how she wanted to keep it cleared and photograph it as a remembrance of the resting place had an admirable vulnerability. She spoke about how the land will not remember a death which occurred on it and how the earth does not care, but artists make that earth powerful and create the death's memory. We can see this throughout time with decorated graves and sites on the streets where car accidents have occurred. No one would know unless it were shown through art. This theme of death and that we will all die one day manifested into an important body of work where she found interest in mummified skin, bones and exposing the texture of death to the world. She sought to emphasize how we need to fully embrace living and life while those you love are still alive in the show she put on through her work. The unfortunate cancelling of this show even hurt me as I watched her reaction. A heartbreaking wrenching of denying the importance of her work. I cannot imagine how this feels, but I do not think it is a reason to stop creating that type of work or diminish its importance in the artist's mind. As she states, when you hit a block, just take a photo. Explore and ignite what strikes you when you travel into your local environments. Inspiration will not come unless you first stop; and observe.

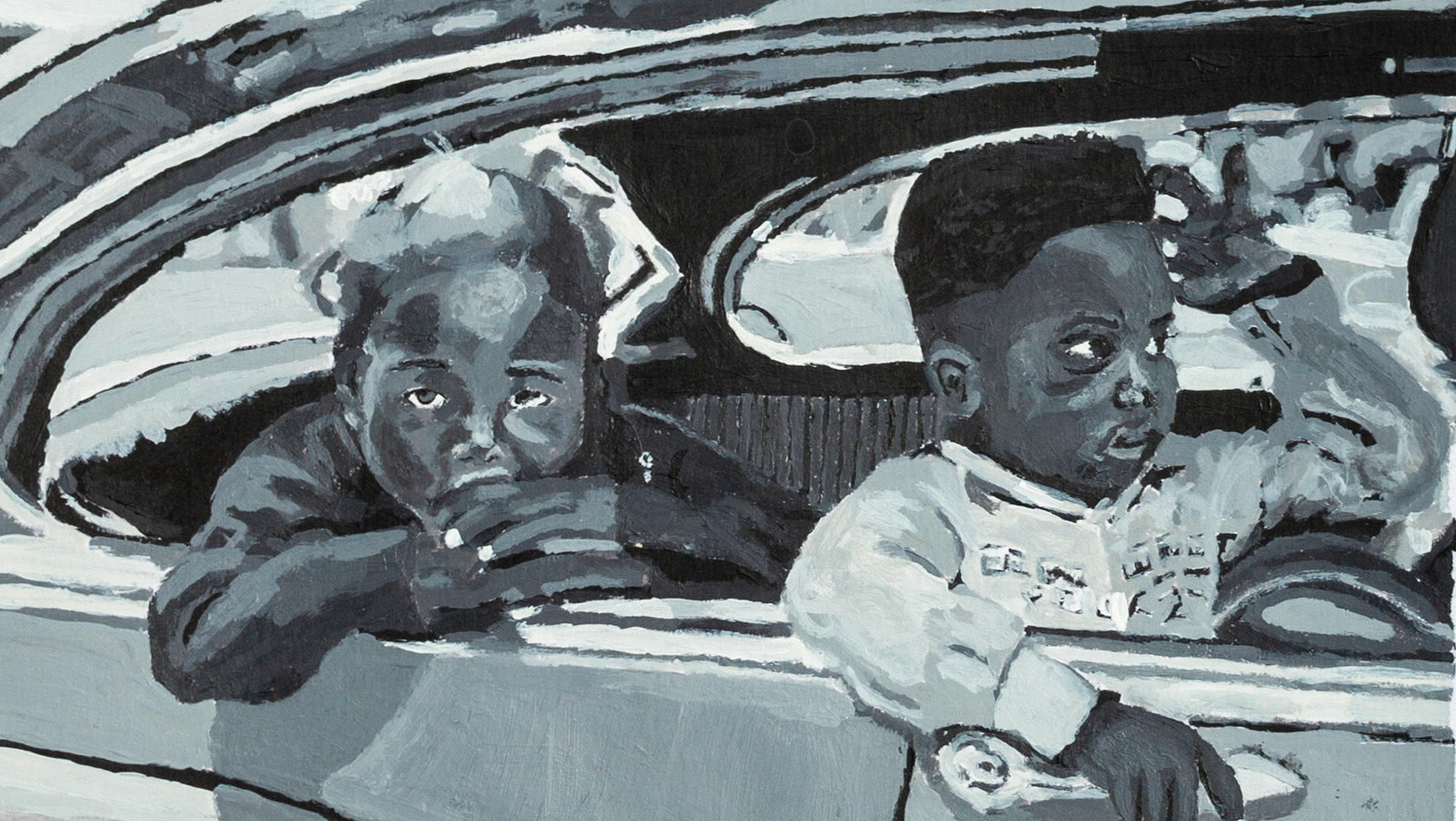

Ask a Curator: Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop

I had never heard about the curator process or perspective before, making this recorded zoom meeting particularly interesting. Seeing how the curators formed relationships with the artists to both understand their work at a deeper level and gain their trust to show their work in the space of The Whitney was fascinating. I had not previously heard of this group, and learning about how they influenced areas like Harlem and taught other young artists in the area was so meaningful. They are individual artists who met regularly and bounced ideas, held debates and learned from one another. Some had gone to University, but not all. It seems as if the group was a safe space of friends who sought to create something unique, intentional and spontaneous during the black arts movement and civil rights movement.

I loved how their portraits were the first things you would see walking into the gallery. Each one shot so closely and matted largely, consequently framing them more distinctly. This represents how they are this collective group with different approaches and styles. I thought it was interesting how this seemed to be a choice of the curators and not the artist to begin the gallery in this way, telling a story about the group. It is interesting to note that the group only consisted of one female, the rest male. They explained it being that way because they group came about naturally from mutual friends, and opened up to becoming like a family. Shooting together as a family or tight knit community sounds like it would be a fun and unique way of learning and growing within each individual’s art. I miss the days when I would be able to go shoot work with a group of my photography class, let alone a group of close friends. On top of all their work they were able to create their own gallery space and put on group shows ranging from portraits, intimate home-life shots, street-shots, gorgeous interior shots, children playing with a background of stark contrast, and people dressed for special events within the African American community.

Talking further on their inspirations, they noted music to be prominent. Specifically Jazz musicians in the era when it was on the rise, such as Miles Davis. This was reflected in their works in the form of dynamism, fluidity, genre bending and experimental projects. I think music as an inspiration is a powerful thing, especially since their work encapsulates black culture and how they view it through different lenses. It is important to find inspiration in many forms of how the culture was formed, what was prominent in the making of it and how it affects the community.

Albert Fennar took a unique approach into abstractness. He explained his method as keeping the goal of going out to shoot with no plan or idea in mind of what to capture. Allowing his eye to catch what felt right in the moments. These images give a certain sense of his reality and open the work to further interpretations and different perspectives. The spontaneity and almost messiness of his photographs speak somewhere so closely to me. His style reminds me somewhat of Vivian Maier’s style, but with more delicacy.

On the other side of the style spectrum landed Adger Cowans who portrayed events during the civil rights era in a cinematographic way. There was one photograph where he highlighted the magnitude of the crowd at a Malcom X event, rather than the man himself, emphasizing the force of the movement. He was able to capture intimate moments as well because he was part of the community. There is a type of strength and power portrayed in this era of his photography.

Fascinatingly, the group was able to reach an international perspective outside of the American context. They were able to explore other countries who had gained new independence from colonial holds. What was especially interesting is some of the members would travel somewhere and stay for years, fully immersing into the community and learning how the people interact and support their artists in different ways. What an intimate way to really become part of a different culture and community. I aspire to this dedication of learning and capturing reality. Furthermore, the relationships they formed expanded to the whole group who held annual dinners with honorary members from different countries. This reminds me that learning is not about getting the information and using it to your advantage, but taking the time to care about what you are learning.

Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters

Gregory Crewdson paints a very unique picture of American suburbia, one which ominously flows with a rich depth. His artistic process, shooting process and post-production process are each fascinating and unique. I think everyone has a need to clear their mind for inspiration or that one idea that is “it.” Recently, I have been doing yoga, meditation and looking at the sky to find my creative depth. Crewdson does so by swimming through a murky lake and getting lost in the rhythm. I think it’s beautiful to find a calmness in the rhythm. And with that rhythm flows an entirely directed scene, down to the placement of a hand, or the position of the car in the street. Crewdson’s images have the ominous mood of the run-down mill towns he shoots in, where he has built relationships with the local people. It is so wonderful how he has a personal connection with where he shoots, and with how carefully he scouts a shot. But more so his images evoke an underlying depth of desperation, hunger, grief. Which is broadcasted on a cinematic scale. The built up of one perfect, quiet moment. An entire set, day, crew and closed down streets to create something with deep purpose. His connections with Hitchcock and the melodrama of everyday life come through so strongly in his work. Specifically his use of water, mist and fog in combination with crystal clear clarity create a piercingly strange quality to his work, similar to Hitchcock’s films. Each photograph holds a lot of emotion based on experience and the preservation of the mystery of domestic life. Which is interesting in itself because everyone lives a domestic life, whether they drown it in expensive goods or live below the poverty line. One may be more comfortable, but everyone is living in a world that is run by routine. Whether that is going to work everyday or just seeing the sun rise and set, the world keeps running whether we want it to or not. In this way everyone is the same. Life comes with fear, strong emotion, big and small mistakes, wants, needs, beliefs, love, struggle, and that’s only to name a few. Of course disparities and discrimination make some people’s lives harder than others, which is a huge problem; but to our core, we are all human beings. I believe Crewdson captures this humanness in the emotion and process of his photographs.

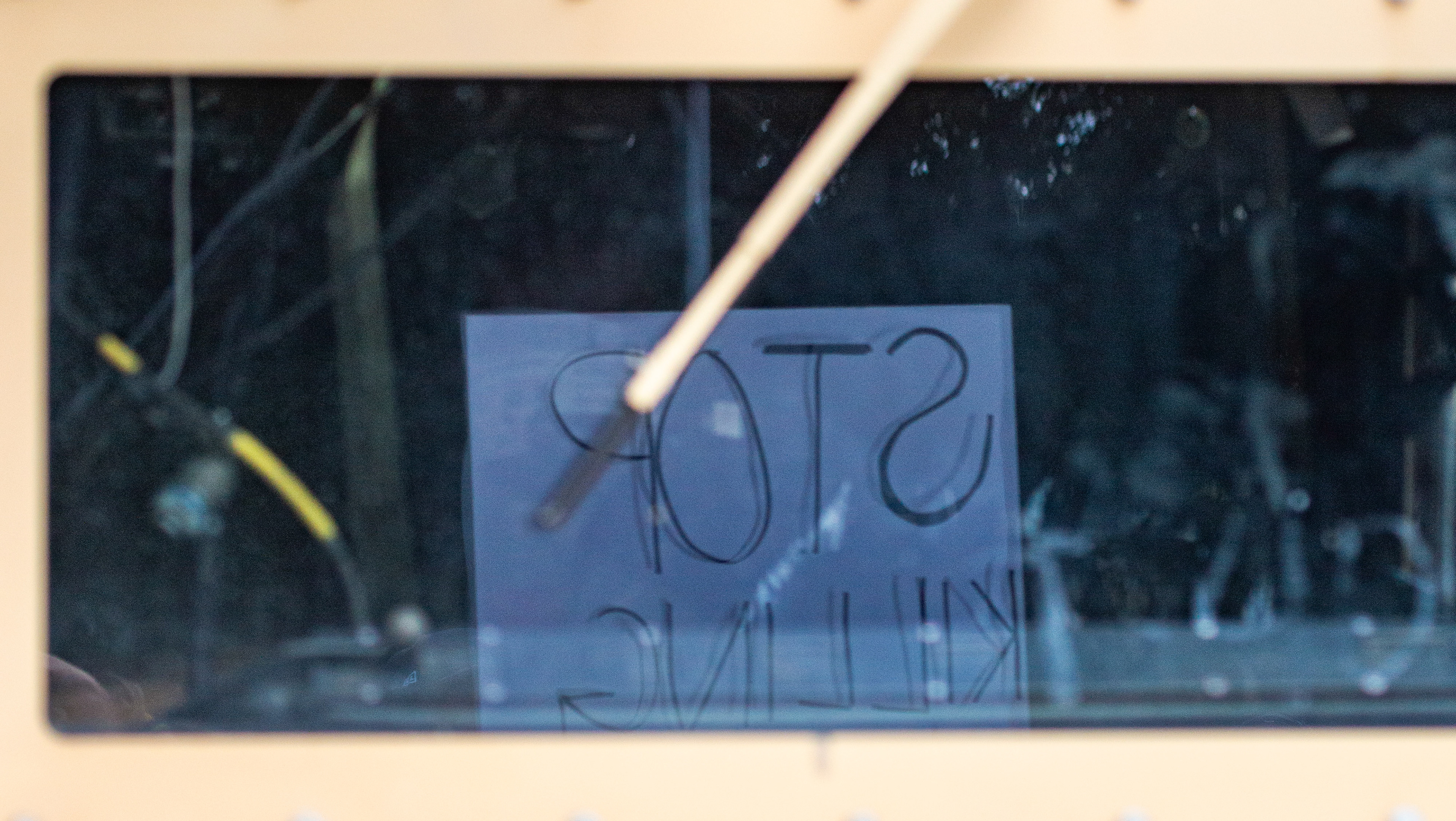

Art 21: Protest

This episode was very intriguing in the way that each artist viewed conflict, war and protest in different ways with various interpretations, but each had a similar view in the sense that art can be an impactful message open to interpretation and experience from ideas and experience. Beginning with Nancy Spero, the way she created art with an archaic, hieroglyphic feel to it opened her work up to a unique perspective. I really enjoyed the first work they briefly showed in an underground subway in New York City. Art integrated into society has an unexpected impact and is available to everyone who rides that subway, which is amazing. Spero hopes her work is not an easy read, and she definitely achieves this. I can see aspects of pain, conflict and longing within the symbolic faces and gathered bodies. I am particularly drawn to the tangibility and physical rendition of her Maypole and its connection with the sounds she imagines of jail cells clanging shut by creating the disembodied heads onto metal; as well as the passion within her piece that was inspired by the passing of her partner in life which she described as the cry of the heart. The subtle despair and reaching of the hands interprets easily as distress, but the reason and pain behind it is widely open. Spero’s view on war overall seems to be that it is painful and unnecessary.

I am very interested in An-My Lê’s perspective and translation of war. She views it with mixed emotions, stating that it is not black and white and therefore very complicated. The overall purpose of war, to her, is terrible, but would not consider herself categorically against it. She takes a direct approach in exploring the idea of war through it’s preparation. I thought it is funny how she described her camera as her way in to explore military preparation. Particularly, I enjoy the way she approaches her work. Each piece forces her to resolve questions such as “what is it like to live in a time of turbulence,” which then grows into each new body of work, resolving questions but furthering the need to explore new ones. When she went back to Vietnam to explore the idea of homeland through memories, smells and photography it was intriguing to see the way she portrayed the people’s affect on the landscape. I think also that the idea of smell is very important to the experience, which artists wish to show the audience and will never translate exactly. The way that she allows the scene to carry and never has full control portrays some type of history on the landscape and within the people of the land. Specifically her shoot in twenty-nine palms which portrayed the military prep for Iraq and the vastness of the land in comparison with our insignificance was magnificently humbling. Throughout her work she maintains that having activity going on within the work is necessary for the message and ideas she holds inside her.

I see such a wholesomeness within Alfredo Jarr who believes in the power of a single idea. That art is arriving at the essence of what you want to say. This resonated so strongly for me because I feel I have so many ideas and things to say, which for Jarr takes the imagination of research, information, and tragedy. His first impulse comes from the need to respond to real life events. This form of protest is the most active and intriguing version to me. After growing up in the divided country of Chile from the age of fifteen Jarr became passionate about tragic events. Particularly, the tragedy in Rwanda and it’s underrepresentation in the media struck something within him that caused him to need to visit refugee camps and show their story-- in the right way. He struggled with presenting the people and situation accurately and respectfully. I think as an artist the marriage between passion and presentation is the most difficult aspect of creating. There is no perfect way to communicate the experiences we feel and live to other people, and it is inherently impossible. I enjoyed how he viewed the gallery spaces as somewhere others will enter into a specific model of thinking and looking at the world. It is an experience within itself. Jarr’s need to communicate a very specific amount of information to his audience is essential to how the work is received and able to be interpreted by varying perspectives. I am intrigued by his need for the logical and for the work to make sense because it connects the abstract of his work into the original idea. Additionally the importance of incorporating beauty into work because it is a part of life without staying with it or being afraid to confront beauty and horror is inspiring. I loved his piece which displayed a hundred flowers subjected to the contradictory forces or water, light, industrial fans and cold conditions. The poetic balance of continuously dying and being replaced, as we all are is both calming and a discomfort. Jarr’s view of art as an experience we portray as another experience for others reminds me of how important the way in which work is shown is essential to the message behind it.

Holtz works much differently than most artists with short packed work streaming across buildings and billboards, or on the ceiling of rooms. The messages are short because of the nature of viewing, passing by quickly from the street. This commands attention and a wider audience, widening the impact. I think the statements she makes are strong and give what can become a mundane lifestyle in the city a pop of excitement, which turns into introspection or communication about what was seen. The nature of these exhibitions require very powerful projections for visibility and readability, emphasizing the theme of power before the message even comes across to viewers. Eventually she found it difficult to say enough adequately and began using others' words and taking creative liberty in the visualization, colors and omissions for the work. These aspects are extremely important to the connotation and message the work puts out for interpretation. Her work which was projected on the ceiling of a building with many glass windows created beautiful reflections and commanded attention within the space, especially since it could not be read without laying down and viewing the words streaming vertically rather than horizontally. This was such a unique layout for the work, elevating words into an exhibition. Lastly, her work which dealt with government documents was especially interesting due to the blacked out portions that were blocked and hidden from the public; many were regarding the military. She chose the sizing and coloring over the words to convey a specific message and mood to viewers based on the subject and mood of the letters. I would love to work with words one day but have never thought of it too deeply. These methods are unique and commanding in subtle ways which intrigue people rather than scare them away.

Art 21: Time

I have always had a special interest in the concept of time and how it is experienced and defined by human beings throughout time. This episodic documentary highlights artists who explore the experience of time through the experience or method of their art. Shortly and sweetly Merce Cunningham introduced the idea of the expression of time through tap dancing. I had to think about this for a second and realized any type of experience is a passage of time. It is ever moving and changing, never stagnant.

Martin Puryear found an interest in vernacular cultures where the people are close to the materials and create things for use in a utilitarian way. This form of creation is not artistic, but functional. He took the functionality of a piece and formed it to speak in a deeper way. His cascading ladder worked with the illusion of an artificial perspective which appeared to leave the space faster than it really does. This translates as a metaphor for the view from where you start to the goal you wish to achieve. In this way, work itself is the information. The labor and time it takes to create forms the representational tendencies that the work embodies. Puryear’s work of the grotto which forms two halves-- one you can look but not enter giving it a mysterious quality and the other a projection into space with a more aggressive, masculine connotation. His interest in stone specifically is fascinating because the material connects strongly with the earth and is difficult to carve and change. He speaks briefly about the difficulty to give up some control of his work, and how it ultimately opens the work for input that improves it in ways he could have never imagined. I think having the opportunity that someone is so interested in your work to comment and contribute is a wonderful connection and influence to welcome into the process. This is seen in his stone work of the colossal head. This work is huge, heavy and intricate, coming directly from China and shown in Japan. He had to put his trust into those he was working with to form the intricate blocks he would connect to create the final product, using a hand chisel to work closely with the material, as well as adding texture. I am in awe of his interest in organic forms, natural processes and cultural forms which influence the process of creating and making by hand.

Diving into domestic interiors, Paul Pfeiffer was influenced by the uncanny and horror such as Amityville horror. His work is intriguing because of the combination of a large real time projection with a peep hole look into the real diorama from different perspectives. The projection is from the top of the staircase and the peephole from the bottom. The idea of setting up relationships between objects, images and people for viewers to experience the connection between oneself and another in seemingly different realties is extremely intriguing. I was surprised to see his next work involved our connection with television, straying from the horror element and into the evidence of erasure. I resonated strongly with his description of working frame by frame, erasing pixels and modifying images becoming meditative because you have to achieve a certain kind of focus, as I have been working with erasing pixels recently. Additionally, the looping gifs he created draw in the viewer because the loop does not reveal why the things happening are happening in the repetitive sequence in the same way we watch the repetition of fire. Lastly his piece “Morning After the Deluge” connects strongly with the idea of time in the sense that the loop of the sun setting and rising projected on the wall takes an entire twenty minutes to view. The loop exemplifies slow movement and our relationship with the accessibility of time. This made me think about how the inequality of wealth is directly linked to the inequality of accessibility of time.

The layers of work and time put into Vija Celmins’ pieces gave them a quality of memory. The dense feeling after nine renditions of paint on top of one another exemplify her relation to her work as building the painting. It is visceral and personal. I am fascinated with her instinctive desire to recreate texture and detail in the rocks she found in New Mexico and the idea of being the creator. Moreover, I connected with her idea that things unconsciously seep into the work simply by spending lots of time with it because time has more of an effect than just passing by. I used to think time was just a stupid construct, but could it be something valuable that we can reclaim as a society?

The motorized contorting face of Tim Hawkinson immediately caught my eye as it connects the science of physics with art. I used to feel very connected with physics before I dove into my passion with art in the hopes of one day connecting the two. My path may be different now, but it is amazing to see this connection drawn by others. He calls the center controlling the changes and picking up the light and dark patterns to trigger motion in the face as the brain. I always find people’s nicknaming for their pieces very fascinating as it reveals something about them in an uncanny form. Hawkinson’s abstraction of bodies, identity and experience through the representation of recognizable forms in strange forms with nonhuman components constitutes our relationship to the external world outside of our bodies in an interesting manner. I think abstraction is important to our concept of life and what it is to be alive. When he moved to incorporate sound into his work from the accidental dripping of water through the ceiling I was amazed. What a fun way to find inspiration through the stimulation of another sense. The connection between the rhythmic drop and air noises and the religious musical scores he took inspiration from are not obvious, but integrated into the work. I enjoyed how he created models to ensure his work would fit in spaces and work as intended, because the mechanics behind the structures are just as important as the space they fill. The time it takes to experience the music and rhythm from the structure connects viewers to the idea of the experience of time itself.